How do we learn language? Children do this without effort. Adults usually need grammar and dictionaries to learn a language.

How can computers work with language? The classical Natural Language Processing (pre ChatGPT) works like adults learn a language. The computer is given a list of nouns, verbs, grammar rules, word order and some other rules… and many years of research to make it work. Somewhat. That’s why ChatGPT was such a huge surprise. AI can have a pretty good conversation these days. Large Language Models, the specific form of AI that makes it talk, learn a language without grammar and word meanings. How is that possible?

Topography and grammar

At school we did not only learn foreign languages. There was also geography. Topography! Learning maps by heart. This is not neede anymore: navigation apps lead us from A to B. Google Maps, TomTom and friends have learned topography like we learned foreign languages: using lists and rules. What cities are there? Which connections (roads) are in between? Where can you drive and how fast? That’s a lot of work! What if we don’t have those lists and rules? What if we do not have a map available?

As a child, I learned the roads of my village by walking and biking. When you move to another city or even a country, that is much harder. Like learning your mother language does not cost effort at all, and German inflections are a bit harder (for non-Germans).

A Roman cartographer

Imagine a time traveller comes to visit you. Let’s invite a Roman cartographer this time (in stead of the medieval guest in my first blog). He does not know The Netherlands and does not know about modern ways of transport. But being a cartographer, he wants to get to know the country. You invite family, friends, neighbours and colleagues to tell stories about the Dutch topography. (It’s good that Google Translate can also handle Latin!)

Day after day, the travel stories are told: from Maastricht to Nijmegen to Utrecht. From Groningen, via Zwolle and the polder to Amsterdam. From Leeuwarden via Sneek, IJlst, Sloten, Stavoren, Hindeloopen, Workum, Bolsward, Harlingen, Franeker, Dokkum back to Leeuwarden. From Zurich to Den Oever. Etcetera. (I considered to change this paragraph to another part of the world, but the non-Dutch reader will now have a similar slightly bewildering experience as the Roman cartographer.)

Your Roman friend hears all these stories and over time, he gets an impression on the Dutch topgraphy. Based on reported travel times between places, he can probably put the places on a piece of paper in such a way that they fit the travel stories.

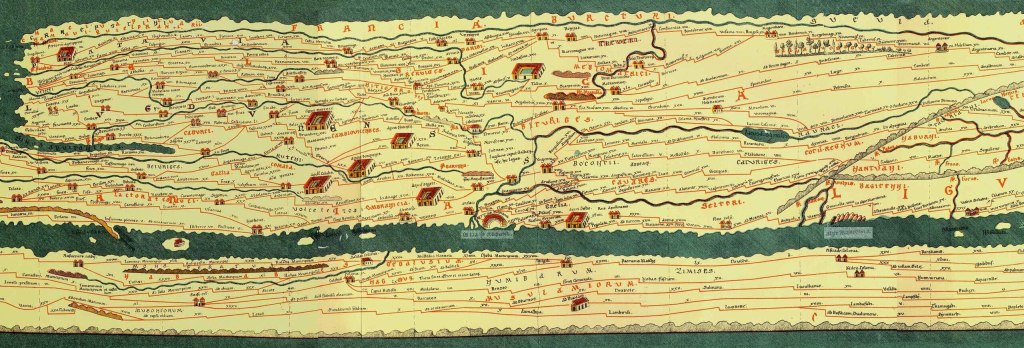

Funnily enough: such maps exist. The famous Tabula Peutingeriana is a map of Europe that mainly outlines the connections between cities, through trade routes and pilgrim routes. The shape does not really match how we see Europe today, but for the goal it works.

A Roman map of the Netherlands

Our Roman friend, let’s call him Gaius Publius Tiberius, will base his map on two dimensions: horizontal and vertical, X and Y, north-south and east-west. When the map has to be more precise, he could add dimensions. Besides locations of places and their connections, he could add data that identifies the type of connection: a footpath, bikepath, road, highway… maybe also canal, ferry or air connection.

Based on the travel stories alone, smart Gaius could figure this out without knowing about modes of transport. Some travels cost 30 minutes to get from The Hague to Utrecht – that must be a highway, even though Gaius does not know what that is. Some travels cost much more time: from Pieterburen to the Saint Pietersberg costs 26 days – at least according to the travel stories. That pace is clearly not a highway, and Gaius will feel more familiar with this. He will produce a map on which places are drawn reasonably accurately, with roads in between that indicate how fast you can travel between them.

You can create a language model in a similar way by giving huge amounts of text, the training data, to a computer. Every text and every sentence is a kind of ‘travel story’: specific words are set in a specific order. Which words follows which other word, taking into account all previous words? When this has been charted precisely enough, ChatGPT can give a ‘logical’ answer to your question. Note: this is done without the computer’s ‘knowledge’ of the word meaning!

You do not only need connections between cities, you also need districts and addresses.

That is what language models also do: they don’t use comlete words, but ‘tokens’: parts of words. Also, language models track which ‘further away’ sentences and words are frequently occur together and which combinations are essential. That is the ‘attention’ mechanism (maybe more about that later). Compare it to travels between The Hague and Rotterdam: you can take the A4 or A44 highway – they will both take you there and are both logical, but the actual choice will depend on traffic jams.

How does the language map look like?

Just like Gaius could represent all cities and villages in the Netherlands based on numbers (positions on the map), it is also possible to catch words in a language in numbers. The Roman cartographer could easily identify that places always have an X and Y coordinate; after that, it was just figuring out the exact values. The fascinating trick that Large Language Models perform is that we don’t have to tell them which numbers they have to use to ‘put words on a map’.

Using ‘deep learning’, AI can figure out which numbers can best be used to put words on a map.

Deep learning is inspired by the way the human brain works: connections between neurons that can become weaker or stronger over time. The deep learning model is trained by making large numbers of intermediate calculations on the input, the training data. The output of the model will initially not be good at all: the quality of the map is not consistent with the travel stories. By making small corrections in those partial calculations (making connections between neurons stronger or weaker), the end result becomes better over time. When you have enough training data and you know what the output of the model should be, you can adjust the model in such a way that it does not make big errors anymore.

Who wants to dive deeper into deep learning and has a very little bit of math on their sleeves, should read this brilliant introduction: Hello Deep Learning: Intro – Bert Hubert’s writings

This process is what is also called ‘self learning’. How can you do this with language? You just have a big amount of text. How can you say ‘this is right, this is wrong’? The trick is to ask the model to ‘predict the next word in the sentence’. The training data already tells you what the next word should be. That is why LLMs are also called ‘word prediction’ models, or ‘autocomplete on steroids’.

There is one big drawback, though. You really need a lot of training data. A lot of it. That is why it took so long before the deep learning method led to practical results.

So, Large Language Models make their own ‘map’ of a language. Based on all training data, they have a statistical model of the popularity of words, sentences, and their combinations. When you look under the hood of such a model and when you try to interpret the map, you can observe patterns. At least, in a number of cases. A popular example is “king – man + woman = queen”, although in practice it is a little bit to good to be true. Nevertheless, you can even discern patterns that relate to more abstract concepts, like researcherf from Anthropic showed: they could see the concepts ‘program error’, ‘gender bias’ or ‘secret information’ quite well.

How does this help?

It’s good to realize that Large Language Models like in ChatGPT contain a very big language map, and have some kind of ‘navigation app’ to plan more or less logical routes in this space. We can make fun of people who trust their satnav blindly and take very special routes, but we should realize that ChatGPT can take us into similar stupid directions when we don’t pay attention.

It’s also good to know that the map of Gaius Publius Tiberius is based on travel stories and not on observations in the field. In the same way:the language model is based on training data and does not know anything about reality. It’s all nice that all kinds of world knowledge emerge from the training, but essentially, it’s just a map.

There are more questions. Dit Gaius really hear all travel stories? Did the language model get all different types of texts? More about that later.

Like George Box put it very nicely: “all models are wrong, but some of them are useful”.

Plaats een reactie