How is AI made? Sometimes you hear “the Chinese make the computers, the Americans make the software, and Europe makes the laws”. Isn’t it better that Europe also focuses on making AI software and models, and focus a bit less on legal and ethical stuff?

When I started my study Electrical Engineering back in the day, I could not imagine that such topics could ever relate to legal things. The other way round was similar: the faculty of Law where my wife started her studies, was the last at that university that did not yet use computers – and they took pride in that.

This has changed. When one of my children started a study on Food Technology at Wageningen University, and specialized in food safety, I suddenly saw very thick books titled “Food Law” being carried around. I then realized that food safety is a useful metaphor for the (still quite) abstract conversation around the AI Act.

Thanks to the enormous amount of innovation in our food supply that was made available after the war (mainly thanks to Wageningen University) we now have plenty of affordable food. It’s very safe, too. Food that is for sale in the Netherlands can be put into our mouths without concern: it is not contaminated by strange substances, allergens are indicated on the label. The long-term health effects are arranged, too: besides the nutritional values table, there’s now also the Nutri-score. You can still eat unhealthy, but with a little bit of background knowledge you are able to figure out a healthier choice by yourself.

How different is this with data and AI. These also have become available in huge quantities after the dotcom-bubble in the 2000s, mainly from Silicon Valley. We now have plenty of free services. However, we do not really know whether they are safe. Can we put all that information into our heads without concern? Where does it come from?

Is food healthy and safe? Is AI responsible and without risks?

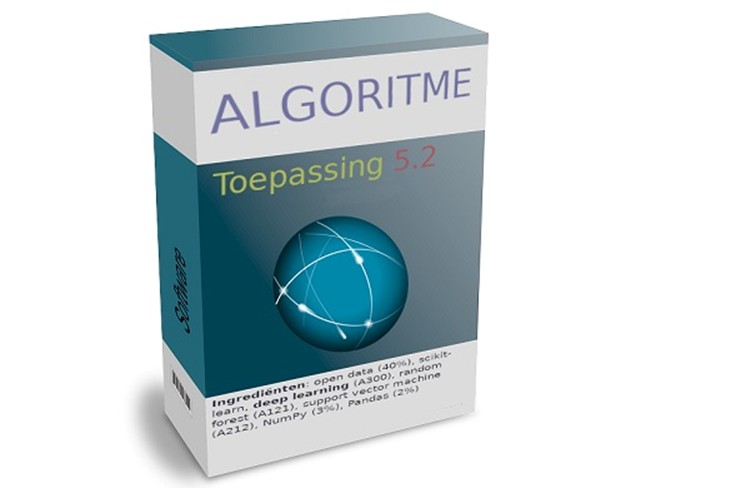

There is no ingredients list for AI. It is not clear with what recipe it was created: a Large Language Model that has been trained on strange texts, or a social media algorithm that draws you into a desert of misinformation. The mental health effects on the longer term are not precisely clear. What is the ‘nutritional value’ of the output of AI?

In the second half of the 20th century, when food was produced increasingly at an industrial scale, we lost sight on the production of it and we imposed strict rules on the food industry. Additionally, the consumer had to be educated: what are kilocalories, what are proteins? Because safe food does not automatically mean healthy food.

Therefore, it’s logical that the European Commission wants to regulate our ‘food for thought’ in the same way as ‘food for body’. For high risk AI applications, strict rules have been established for the ‘factory’: the producers have to give insight in the production process and the ingredients (the training data). There is a labeling requirement for AI systems that directly interact with people.

Remarkably, sometimes not only the end product, but also the way it is created is also regulated: there is a special category with special rules for ‘general purpose AI models’, like ChatGPT. This was added in a very late stage, when the AI Act was already largely designed.

There is also some kind of Food Authority: besides the European AI Office, in every EU member state there will be an authority that supervises AI. The most important supervisory activities are arranged nationally, but some tasks are done by the AI Office, like monitoring general purpose AI. The reason for that is that there can be a so-called ‘systemic risk’: such types of AI have a big influence on the information that citizens are receiving; and, consequently, their mental health. There is some logic that this is done at EU level.

This way, we can arrange that the output of AI systems is basically safe and that it remains that way.

However, just as we expect that home cooks have basic knowledge of food safety, it is necessary that AI users have some background knowledge as well. What is an AI system anyway? What can we expect, what not to expect? What’s the difference between data, a model, the user interface? In short, we need ‘AI literacy’.

For this, citizens do not need to become programmers. Just like we don’t need to be food technology experts to understand that an opened jar of pickles will start to rot when not kept in the fridge. (We know that we’re heading in the right direction when The Great British Bake-off has an AI version like The Great British Prompt-off or something.)

It won’t be perfect. Just like the Nutri-score is not sufficient; and even if it were: people can still make the choice to only eat unhealthy food. The AI Act will not completely get rid of misinformation and fake news – but it’s certainly a step into the right direction.

Plaats een reactie